It would seem the belief in life after death is as old as spirituality itself. However, the great beyond hasn’t always been considered a heavenly place: at first it was perceived as an ominous realm, the house of darkness. To discover the origins of religious rites it is necessary to investigate prehistoric burial sites from an archaeological perspective. Here are some findings.

The oldest written records describe various forms of life after death. The atheist consensus is that the belief in immortality – or religion in general – was established as a form of wishful thinking, a kind of compensatory self-deceit pursued to counter the horror and inevitability of death. However, this argument can easily be put aside if one looks to the history of religion.

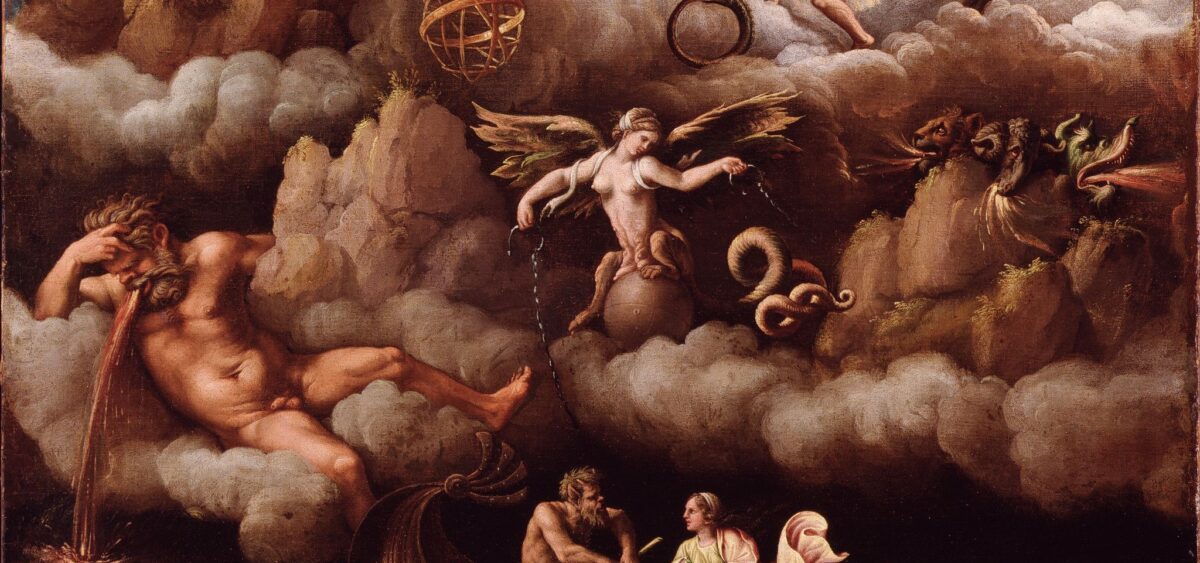

The first descriptions of the great beyond written down by the Sumerians and Akkadians do not mention any place of eternal happiness. The ‘other world’ of ancient Mesopotamia is a subterranean land of no return where the dead stay in a depressing darkness, unconscious of their own position. Covered in dirt, they eat clay dumplings and quench their thirst with murky water. This afterlife is not called ‘heaven’ or ‘paradise’, but ‘the house of dust and darkness’. Everyone except gods and heroes ends up in it – even kings. The fate of the dead improves slightly if the living remember about them and, for instance, bring better food to their graves; the worst off are those who are completely forgotten (this should explain the importance of the burial rite).

As is well-known, however, both the ancient civilizations of the Middle East and all other civilizations are a novelty in the history of mankind. There are reasons to think that the belief in life after death is much, much older.

The vast period of prehistory is usually delimited by the invention of writing. It is an unfortunate criterion, because it is often underpinned with the value judgement that those who write are better than those who don’t. Trouble is, in some regions writing wasn’t used until modern times. For this reason, the periodization of history is Western-centric, or, to be precise, Middle Eastern.

On the other hand, the appearance of