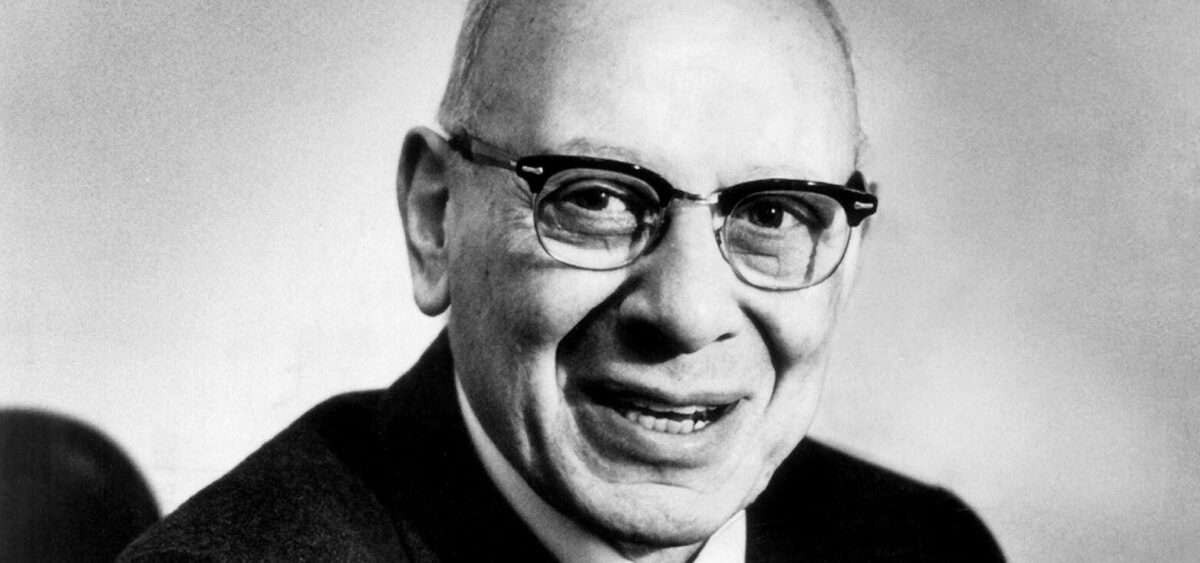

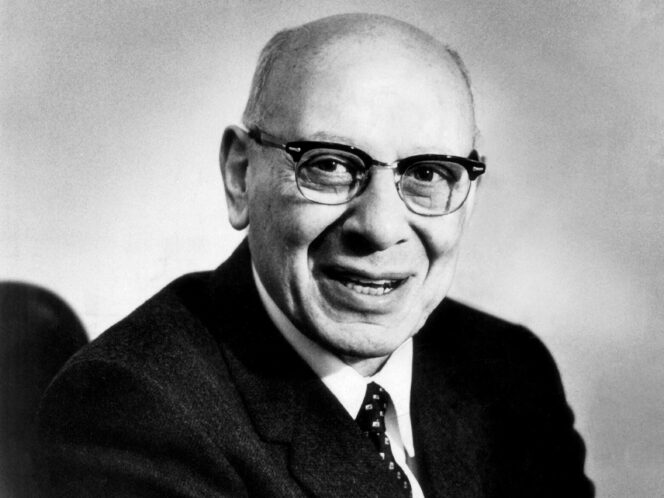

One of the most harmful views we have accepted is the belief in the superiority of the mind over the body, the psychotherapist Alexander Lowen claimed. How can there be any superiority if these are two sides of the same coin, equal and inextricably bound together? To cure the psyche, one needs to care for the body, too—and vice versa. This conviction became the foundation of Lowen’s bioenergetic analysis—a therapy method based on movement, touch, and the breath.

“You’re not breathing, Lowen!” The half naked man lying on the table tries to comply and breathe in more air. For a while, the silence in the room is only broken by the increasingly loud sounds of inhaling and exhaling. Suddenly the silence is punctured by a piercing yell—so loud that passersby outside raise their heads to see where it’s coming from. The window is open, it is the summer of 1942, in Europe the Nazis are regaining advantage on the Eastern Front, but here, in New York, the war is hardly present. Dazzled by his emotions, the thirty-two-year-old Alexander Lowen tries to sit up, but the therapist, Wilhelm Reich, asks him to go back to breathing. After a while, however, it is clear that on that day the patient is unable to breathe without yelling. The session is over.

Several decades later, Alexander Lowen, already a renowned psychotherapist, the creator of a pioneering therapy method—bioenergetics—came back to that event in his autobiography Honoring the Body. He recounted how surprised he was by the yell, because he was not afraid of anything during the session. Instead, he remembered feeling the mind was not connected with the body, and the yell was a signal to free his emotions and repressed memories. The session with Reich made Lowen realize that he had to face the unknown aspects of his identity.

In the early 1940s, Wilhelm Reich, Sigmund Freud’s infamous disciple, gave a series of lectures on his new theory, according to which psychological diseases could be cured through working with the body. Alexander Lowen was one of the students closest to him. At the end of the course, Reich invited Lowen to work together conducting psychology experiments. He gave Lowen only one condition: the student had to undergo psychotherapy. Lowen agreed but reluctantly. His attitude changed after the first session—the one where he emitted the unexpected scream. During the ensuing two and a half years, he met Reich several times a week to do therapy and to yell many times more during their breathing sessions. Even though a few years later they would part ways, Lowen would