We sent our special correspondent Łukasz Kaniewski to find out more about the problem of plastic debris polluting the Baltic Sea. Turns out it’s not so bad, but it’s not great either. We must protect the sea – mainly from ourselves.

“Oh sea, our sea! We shall faithfully guard thee…,” I hum, getting off the train in Gdynia. This old mariners’ song has recently become remarkably relevant again. Only now it’s ourselves we need to protect the sea from.

“Humans have so little foresight,” says Dr. Barbara Urban-Malinga. “After so many decades, we suddenly realized that we’ve been creating all this pollution.”

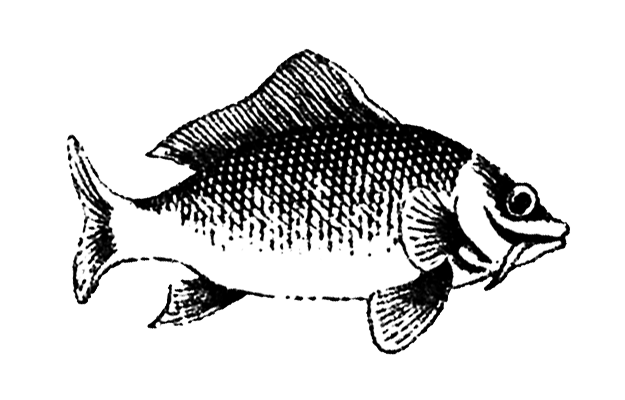

We are sitting in her office at the National Marine Fisheries Research Institute in Gdynia. Urban-Malinga gets up and leaves the room for a minute. When she comes back in, she’s holding a glass lab vial in her fingers. Inside, there is a five-centimetre piece of black plastic bag.

“We found this inside a herring’s digestive system,” she explains.

“How big was the herring?”

“About 25 centimetres long.”

It’s as if someone found an A4-sized plastic bag inside my stomach, I think, feeling a bit uneasy.

“What kind of trash is found most often in the Baltic?” I ask.

“It’s worth mentioning that compared to the rest of the world, we find very few pieces of marine litter. That’s most likely because a few years ago, we organized a large campaign to remove fishing nets as part of the MARELITT project. We removed 300 tonnes of lost nets from the sea. Some people said it would be better if those nets remained on the sea floor and became a bedding for algae and seaweeds to grow on, but considering everything we have learned about microplastics so far, removing them was a wiser choice. Nets, just like any other plastic product, decompose