The ancient Greeks and Romans looked at the same sun as we do, but they saw it a little differently. These seven tales will help us see it through their eyes.

Father and son

This is one of the most archetypal stories. Its protagonists are Helios and his son Phaeton. Every day, the radiant sun god travels across the horizon from east to west, racing in a chariot harnessed with four steeds. He wears a bright crown that we perceive as the sun’s disc. It bestows light and heat on the whole world, causing plants to grow and ensuring all forms of life.

In a fleeting romance with Clymene, the daughter of Oceanus the Titan, Helios fathered a son, Phaeton. But the god took no part in his upbringing, being completely absorbed by his never-ending mission. The boy was therefore raised by his mother, who only told him about his father when he’d become an adult. Phaeton then went to see his father, who, in order to assuage his guilt, promised to grant him one wish. The young man asked to drive the solar chariot for a day. Horrified, Helios strongly advised against it, knowing he was the only one who could control the skittish horses, but Phaeton insisted on getting his own way, to prove he was worthy of being his father’s son. We all know what happened next: the boy couldn’t keep the horses in check and they carried off the chariot, which set alight the earth and sky in its uncontrolled flight. The whole universe was at risk of destruction in a cosmic blaze. To avoid that, Zeus struck Phaeton with a thunderbolt and the body of the poor dead boy fell into the river Po. But what’s this story really about? We have a father who is completely preoccupied with his work, who neglects his son and then wants to make up for it at all costs. And the son yearns to be like his father, wanting to be his equal rather than finding his own path in life.

That’s what universality in Greek myths is all about.

Two sorceresses

The two greatest ancient sorceresses are Circe and Medea. Both come from the family of the sun. The former is the daughter of Helios himself; she lives on the island of Aeaea which lies on the edge of the western ocean. She has great powers – for instance, she can turn people into animals with a touch of her magic wand. The latter is daughter of Aeëtes, Helios’ son. Her father rules over Colchis, in the far east, in a land also called – surprisingly – Aeaea. And though, as we all know, Medea escaped with Jason to Greece, after a stormy life and numerous crimes she returned to her fatherland in a chariot pulled by winged dragons. That vehicle was actually given to her by her radiant grandfather.

And so the sun rises and sets in two lands of the same name, which are the homes of its daughter and granddaughter. Both great, beautiful sorceresses owe their strength to the radiant Helios. This also explains many ancient magical rituals relating to him.

According to Greek papyruses about magic, which were discovered in Egypt, the best time for this kind of practice is when the sun is at its zenith, at sunrise or at sunset. And so it isn’t night time, darkness and the moon that most favour magic, but daytime, light and the sun. And a Greek sorceress is a beautiful woman with seductive good looks, and not the repellent witch who flies on a broomstick and lives in a hut built on chicken legs.

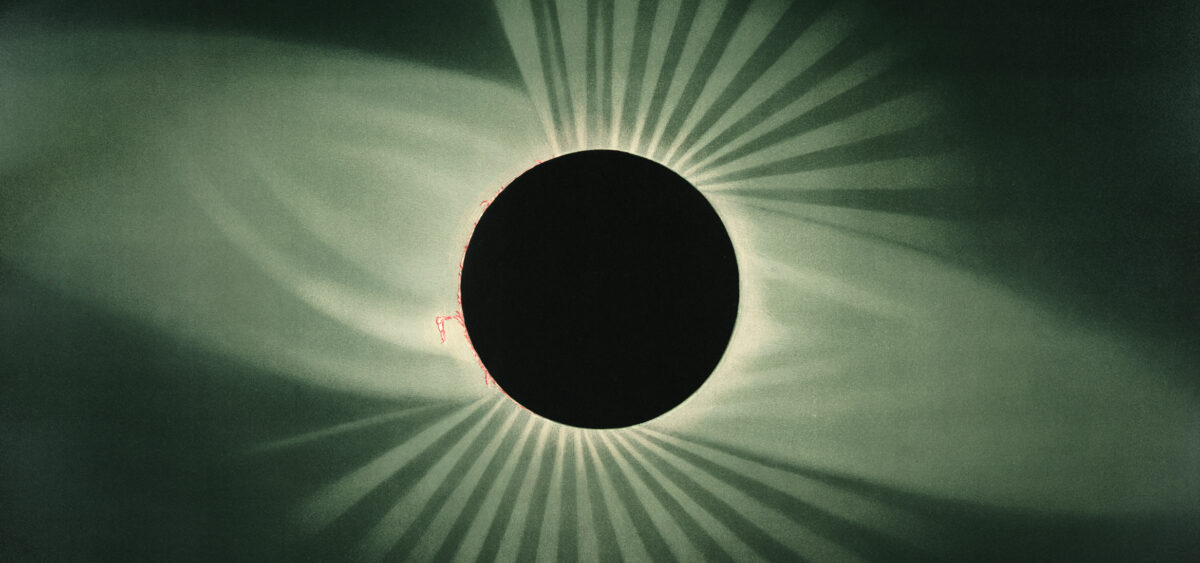

Guardian of the Cosmic Order

One of the oldest known poets, Archilochus of Paros, who lived in the 7th century BCE, left behind a poem inspired by an eclipse that occurred on 6th April 648 BCE. The fact that the sun had disappeared from the sky made him draw the conclusion that nothing on Earth could be considered impossible: we might soon see dolphins frolicking joyfully through the forests and woodland creatures splashing about in the sea. That thought was terrifying – how could you live in a world without any permanent rules? The uninterrupted rhythm of day and night was the guarantee of all order. The sun was its measure. While the sun shone, nothing could threaten us. Why? Because the sun was always there. Even at night. At night, it travelled in the opposite direction, from west to east over the underground kingdom of the dead – or so the Egyptians believed. As for the Greeks, they believed that when Helios’ chariot reaches the eastern horizon, the sun god conceals himself and his harness in a huge spell. It’s like a ship floating on the waters of the ocean surrounding the world, and it’s carried back to the east so that in the morning the god can set off on his journey once again. The eclipse interrupted that rhythm and so inspired fear. But that’s the perspective of people living in the sunny south. For us, people of the north – a dark land where we sometimes go half a year without seeing the sun – eclipses aren’t so terrifying.

Unblemished

Two brothers from a family tarnished by numerous crimes were fighting a ruthless battle for the throne of Mycenae. At the height of the conflict, Atreus killed Thyestes’ sons and covertly fed him the bodies of his children. The cruelty and degeneracy of the human race had reached its peak… On that day, for the only time in the history of the universe, radiant Helios turned back his chariot and headed east, even though the day had barely begun. He did so to prevent the sun’s rays from falling on a world besmirched with such a terrible crime.

An ancient theory of optics underlies this story. The ancients (even the great Aristotle) believed that the process of vision was based on something like ‘particles’ leaving the observer’s eye and meeting with ‘particles’ coming from the perceived object. It had serious implications: could the pure sun god see crimes and misdeeds without being sullied? Christian theologians were also plagued by these doubts, and solemnly wondered whether all-seeing God also looked at animal dung. Towards the end of antiquity, this kind of speculation was exploited in religious conflict. In 394 CE, under the cover of the darkness produced by a storm, the Christian emperor Theodosius defeated the army of his pagan-sympathizing rival. The pagans declared that the sun itself had hidden its face behind the clouds to avoid sullying itself with the sight of the heathen’s triumph. This was said to mark the start of the mediaeval dark ages.

The philosophers’ sun

In the seventh book of The Republic, Plato compared the physical world to a dark cave in which prisoners sit in handcuffs, watching shadows on the wall and believing them to be actual objects. Meanwhile the real world was outside, bathed in the light of the sun. That sun is the image of Good and Beauty, the Absolute. Thanks to its light, real objects are reflected in our cave as shadows on the wall. That doesn’t seem like much? But otherwise we’d exist in total darkness, unable to see anything at all. At least this way, some of us can realize our situation, cast off the handcuffs and go out to the real world to see and contemplate the Truth. Some of these select few will return – out of a sense of duty – to the cave, to tell the prisoners that they’re living in error, that they should free themselves of the restrictive manacles. But the majority of the ‘cavemen’ won’t believe them, because they’re sure the only reality is the shadows they see on the wall. What’s more, they consider those who say otherwise to be enemies, madmen, subversives, heretics, blasphemers…

The sad fate of Socrates, condemned to death by an Athenian court for godlessness and ‘depravation of the youth’, demonstrates very well that these aren’t just theoretical digressions. Each era, each time, has its own missionaries of the light and its diehard ‘handcuffers’ staring at the wall of the ‘cave’. Aren’t smartphones the modern equivalent of that wall?

The eye of the world

It’s the end of the 3rd century CE: the powerful Roman Empire is slowly emerging from a dark period of wars between successive claimants to the throne. The first to experience this first-hand were the Eastern enemies of the empire. In 283, Emperor Carus destroyed the Persian army and conquered the capital Ctesiphon. But he soon died in mysterious circumstances, when lightning struck his tent during a storm. Carus’ son and heir, Numerian, began to retreat, during which he contracted an eye ailment and had to be carried in a closed litter. His procession crossed Mesopotamia, Syria and Asia Minor.

Suddenly, right on the coast of the Marmara Sea, as they were preparing for the crossing to Europe, the stench of his decaying corpse revealed that the emperor was long dead. Mutiny erupted in the army. Those responsible for the death were sought. Those who had access to the leader were his father-in-law and praetorian prefect, Aper, and the commander of the emperor’s personal guard, Diocletian. Both were brought before the army and asked who had killed Numerian. The first to speak was Diocletian: he pointed his sword towards the sun and, taking it as his witness, declared that Aper had murdered the emperor. Then he killed Aper before he managed to say a word. The army therefore decided to proclaim Diocletian emperor. His long reign (284–305), many triumphs and extensive reforms gave a new form to the Rome of late antiquity. But you could venture the hypothesis that he owed his throne to the sun. The meaning and power of Diocletian’s oath can only be understood through the prism of the ancient concept of the sun as the ‘eye of the truth’ – a witness who sees our deeds, intentions, even our souls. Whoever breaks an oath made in that way doesn’t deserve to live beneath its rays of light.

Sol Invictus

For the people of antiquity, the sun was something immeasurable. It dispersed darkness, which was associated with death and all other evils. In iconography, the sun deity was shown on a chariot or a throne, with a radiant crown on his head, a whip for spurring on his horses and a long sceptre with a burning torch at the tip. The whip was especially important because Helios also used it to chase away demons of the night and darkness. It was a magical weapon. This sun god was no god of love and peace.

His bellicose appearance was strengthened during the times of the Roman Empire. At that time, the Greek Helios was identified with the old, belligerent god of the Italic Sabines: Sol. Under the empire, he became the Unconquered Sun (Latin: Sol Invictus), the favourite of military emperors of the second half of the 3rd century. They worshipped this god as the symbol of the triumph of the light of the Eternal City over the surrounding darkness of barbarianism. ‘Barbarianism’ was also figuratively understood as an area of darkness, backwardness, superstition and stupidity. It also referred to those ‘barbarians’ who lived on the borders of the Roman state, for instance, the Christians. Their religion was seen as part of this dark and gloomy sphere. The solar ideology was therefore exploited gladly by the persecuting rulers. When at the start of the 4th century Constantine the Great converted to Christianity, he renounced Sol Invictus, a god he had once held very close. At the same time, many of the solar aspects were transferred to God and Christ. We even celebrate Christmas on 25th December because it was an important astrological day and the symbolic birth of the new sun, which was worshipped as Sol Invictus. And so the new religion stepped into the well-worn shoes of the old one.