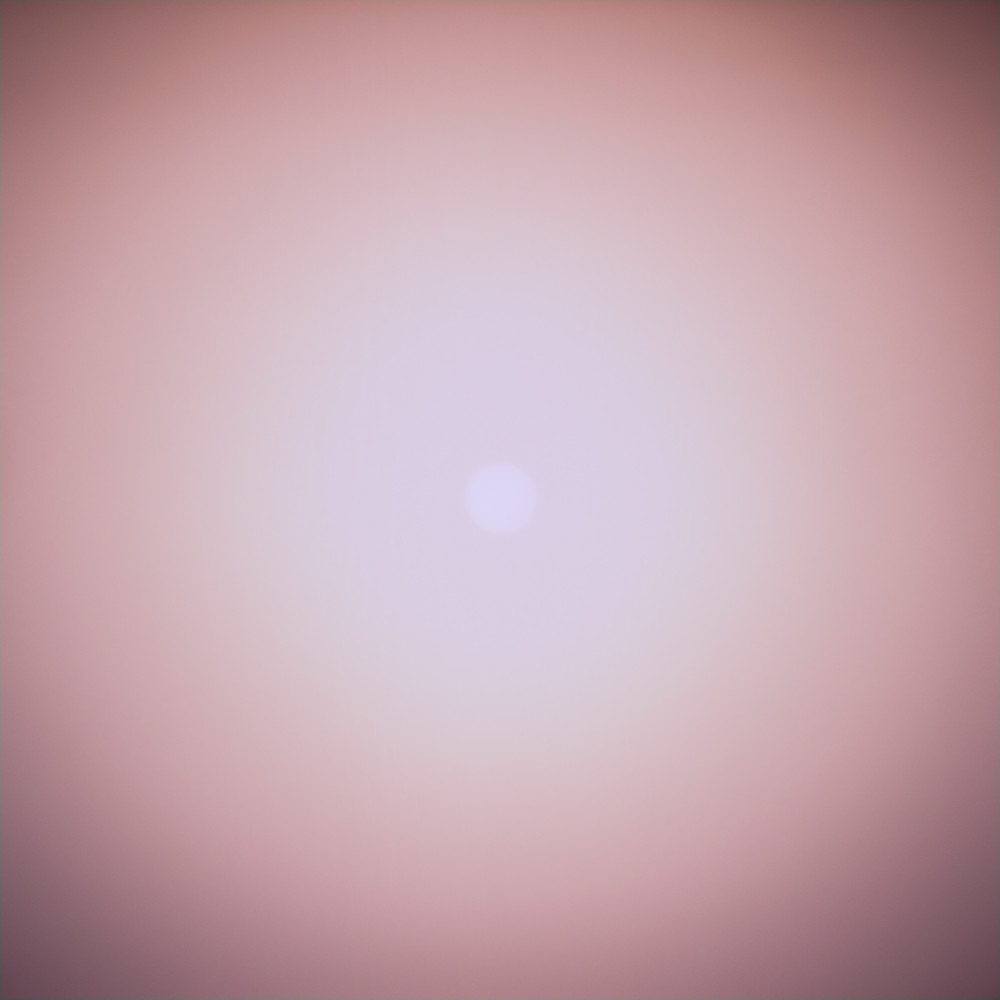

At first glance, one can assume that Igor Omulecki’s works from the Solaris cycle stay within the orbit of post-minimalism and op-art. After all, the minds of the inhabitants of the art world are somehow trained to create such connotations. However, as Władysław Strzemiński put it in his Theory of Seeing: “It is not what the eye catches mechanically that matters in the process of seeing, but the consciousness man has of his seeing.” From this perspective, it becomes easy to understand how Omulecki’s works recall Wojciech Fangor’s painting. An op-art artist as well as an admirer of astronomy, Fangor used to paint the sun – and the works from this cycle were displayed at the famous MoMA show The Responsive Eye.

To curb any further possible speculation: Omulecki’s works in this series are photographs and they present the sun. However, the artist’s aim here is not to analyse phenomenon of light from the perspective of optics. It can be better said that these photographs are the effect of a long-term and consistent circling around and gravitating towards ‘sources of energy’. Yet the artist is definitely not interested in physics. Nor is he interested in the idea that the sun consists of hot plasma shaped by a magnetic field held together by gravity, almost perfectly round. This is the sort of knowledge that we laboriously try to ‘rip out’ despite the limitations of our senses. The artist is not interested in these or any other, more detailed facts. Omulecki puts it simply as: “To watch the sun is the primordial, sensual experience of contact with energy. Looking at the sun usually make us close our eyes; it turns us toward the observation of our own mind.”

Omulecki created his first photographs of the sun in the 1990s. In 2007, he commenced a project called Gym Society. In this video, one can hear a musical background that was originally improvised by free jazz / ‘yass’ musicians (Piotr Pawlak and Michał Gos) to a projection of the film produced by the artist. The film featured repetitive shots with the image of the sun placed centrally alongside other shots of nature’s phenomena received by the eye and re-shaped by the mind into ecstatic sensations. At the time, the artist was continuing his research into unmediated contact with eruptions of energy created by spontaneous group acts, originally practiced in Beautiful People (1997-2001) – his series of performances for camera.

Solaris starts where another project called Family Triptych ended. This monumental series, consisting of such cycles as Lucy 2007-2009, It 2009-2010, Herd Wave 2010-2013, was developed through a long-lasting process that was, at the same time, the artist’s own private journey. It is in this process that we can find the direct sources of Solaris. Triptych searches for the roots, the primordial cosmology. As Jakub Śwircz summarized it: “During the journey, Omulecki’s garden imperceptibly flows into the cosmos. Clouds appear, the moon, finally a nebula of stars. A wide-angle view is shown, and with it, we see the oldest connection with the family, which history the artist only began to learn at the garden’s edge.”

Inspired by this cycle, Tomasz Teodorczyk refers to the transition from primary “yet unconscious recognition that is based on inconsiderate, non-intellectual, pure experience of images,” through “an experience of these experiences,” taming nature through myths, culture and science, to return to “the place from which the whole journey had started – to the image of starlit or cloudy sky which is the first image and experience.”

The next stage of the artist’s development could be observed in such shows as The Universe and Karaoke (both created in 2015) presenting, among others, the first (created in 2013) photograph from the Solaris cycle. The body of works displayed there arose as a result of artist’s radical gesture of going deep into nature, giving up ‘literature’ and embracing realism. The final effect of this process are ‘abstract’ images and sounds.

Even a little child knows that looking directly at the sun is dangerous for the naked eye. To aim at it with an unprotected camera and look through the lens is even more dangerous – for the camera and for the eye. Omulecki clearly knows this. But this project is a culmination of the lonely Ikar’s flight.

It is also a proposal of unlearning, freeing oneself from the knowledge of what, how, and why we are allowed to look.

“Solaris is a journey to the end of the light. The end of the photosopher’s journey. It is the gesture of hanging on the hook the camera – the apparatus used as the ‘hunting’ device that man exploits to show off his technical efficiency. It is also the end of photographer’s ego and the return of oneself to the energy of life sources.”

Michał Woliński