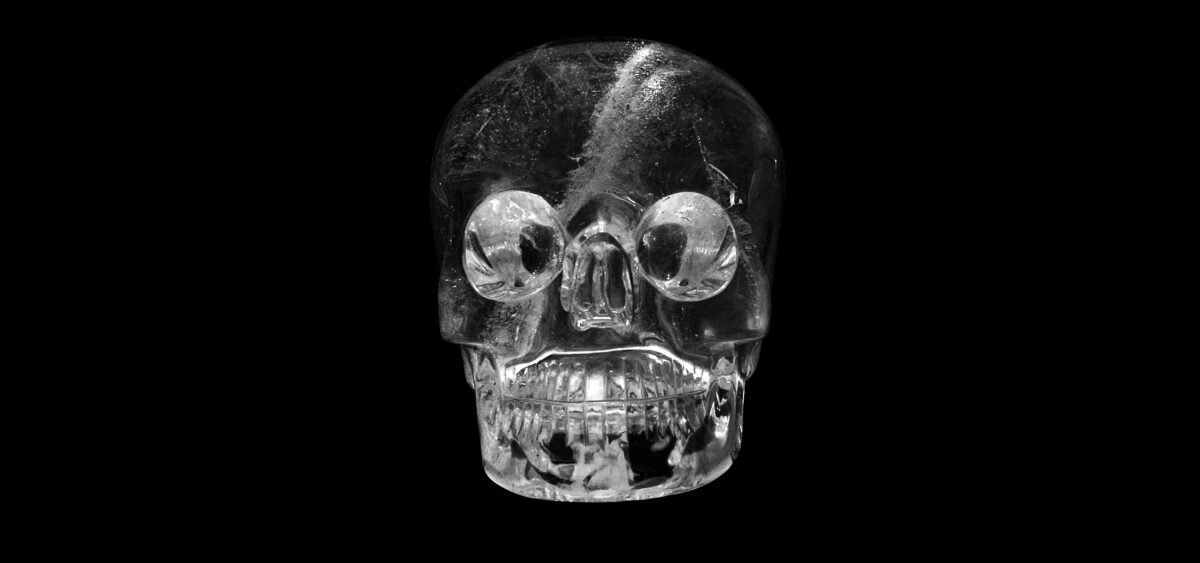

The Romans believed in the power of divination dice made of rock crystal. The advisor to the British Queen Elizabeth I consulted important matters of state with a crystal ball. Belief in the extraordinary properties of this variety of quartz has persisted for centuries.

If a modern person could be transported for a moment to ancient Rome, they would be amazed at how much value rock crystal had for its inhabitants. It was considered a jewel worthy of emperors.

According to the Romans, the mineral’s fragility was proof of its uniqueness. A shattered crystal is irretrievably lost; as Pliny the Elder writes, “the precious pieces cannot be put back together by any means whatsoever.” In his Natural History, the historian known for his passion for precious stones devotes the most space to crystals. In two long chapters, he discusses in detail where they can be found, how they are sourced; he describes their structure and form, and reflects on their peculiar, somewhat opaque transparency.

In the same treaty, Pliny describes the largest rock crystal known to him, gifted by Livia, the wife of Emperor Augustus, to the Capitol—and weighing 150 pounds. The historian also mentions a transaction by a Roman woman who paid the enormous sum of 150,000 sesterces for a single crystal ladle. By comparison, the price of one modius of grain at the time was three sesterces. Pliny also recounts the fate of an unusual stone, an opal, which Mark Antony wanted to buy from the senator Nonius for his mistress, Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt. The dignitary, however, preferred to renounce his family and flee the country