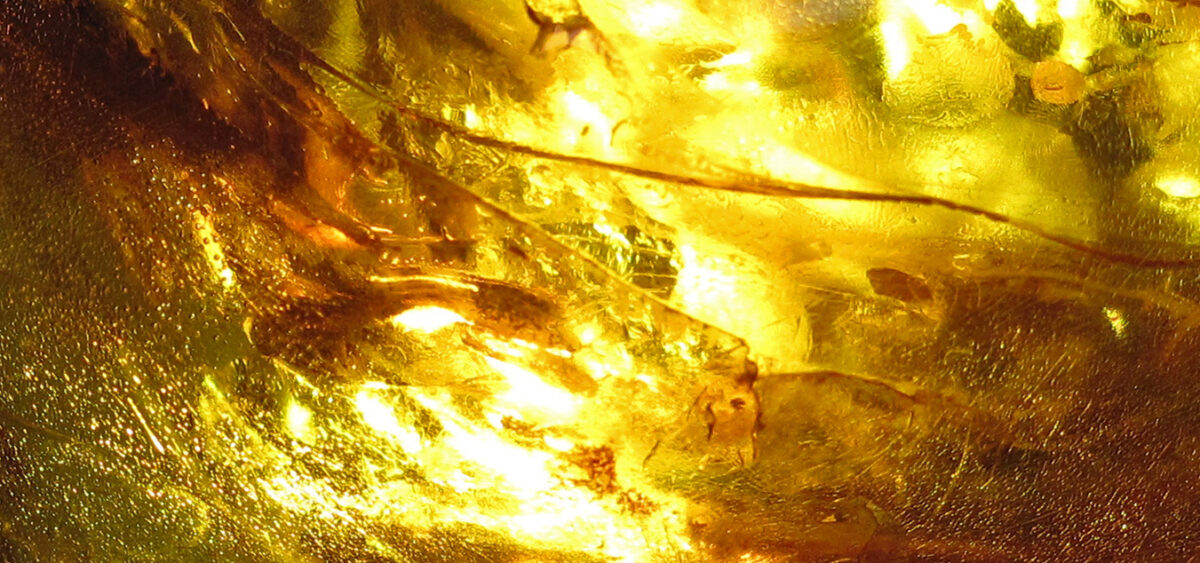

People always loved it for its beauty, but mostly they believed in its power. It was said to cure the ailing, and to assist those in the afterlife. Amber, with its aura of mystery, built a bridge between the living and the dead.

Amber generally has a yellowy-orange hue, though one also encounters whitish-yellow and brown shades, more seldom cherry-red or nearly black. Green and blue specimens also occur—these can be found in the mountain mines scattered around Santiago in the Dominican Republic. Although amber is extracted all around the world, its largest deposits are found in the Baltic Sea region.

The kind found on Baltic beaches is called succinite, from the Latin succinum, as the Romans believed that it came from the congealed “juice” (Latin: succus) of trees. Today it is believed to come from the fossilized resin of various now-extinct trees—a pine (Pinus succinifera), a golden larch (Pseudolarix wehri), or perhaps a species of Japanese pine shrub.

Seeping out from canals under the bark, the resin protects the plant from fungi and insects, safeguards it against mechanical damage, and helps it survive extreme weather conditions. It is assumed that a sudden change in climate—probably a great increase in moisture—caused Baltic trees to excrete this resin in large quantities. This occurred around forty million years ago, in an epoch known as the Eocene, when prehistoric forests covered an area now partly submerged by the Baltic Sea. The climate of this region was warm and damp back then—it resembled more the tropics of present-day south Asia than its contemporary landscape, with mixed-tree forests and thickets growing on the dunes by the sea.

Over millions of years of physicochemical processes, this Baltic resin was exposed to a variety of conditions, fusing with a wide