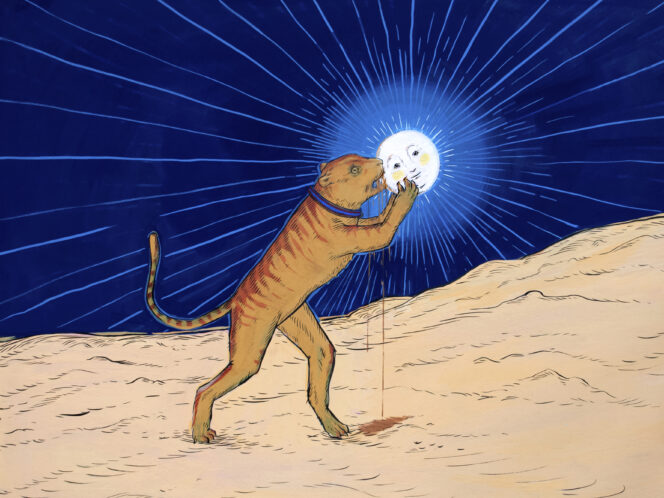

When I’m admiring the last noontime of this year, I know well that the sun won’t rise tomorrow. But even so, I think of it with disbelief—the same feeling I had more than a decade ago, when I saw the polar night for the first time.

In winter, navigating many places in Samiland is childishly simple: as long as you’re going uphill, keep going. Provided, of course, that you have snowshoes because without them there’s no chance of getting anywhere off a paved road; in that case, you can only stay at the foot of the hill, slowly sinking up to your waist in snow, and look up at the summit until your toes get too cold. When you run out of uphill, you’re at the top. Then you can fall into the snow, stretch out your snowshoed feet, settle in, pour yourself a hot drink from your thermos, and admire the view.

The sun barely gets above the horizon. It is morning, midday, and the afternoon, all at once. Everything lasts just a moment—so brief that, even though it’s negative 25 degrees Celsius, you don’t have time to freeze when you’re outside experiencing it, even if you’re lying in a snowdrift. It’s there for just a moment and then the whole show is over, too short for its significance and the change it brings. It would