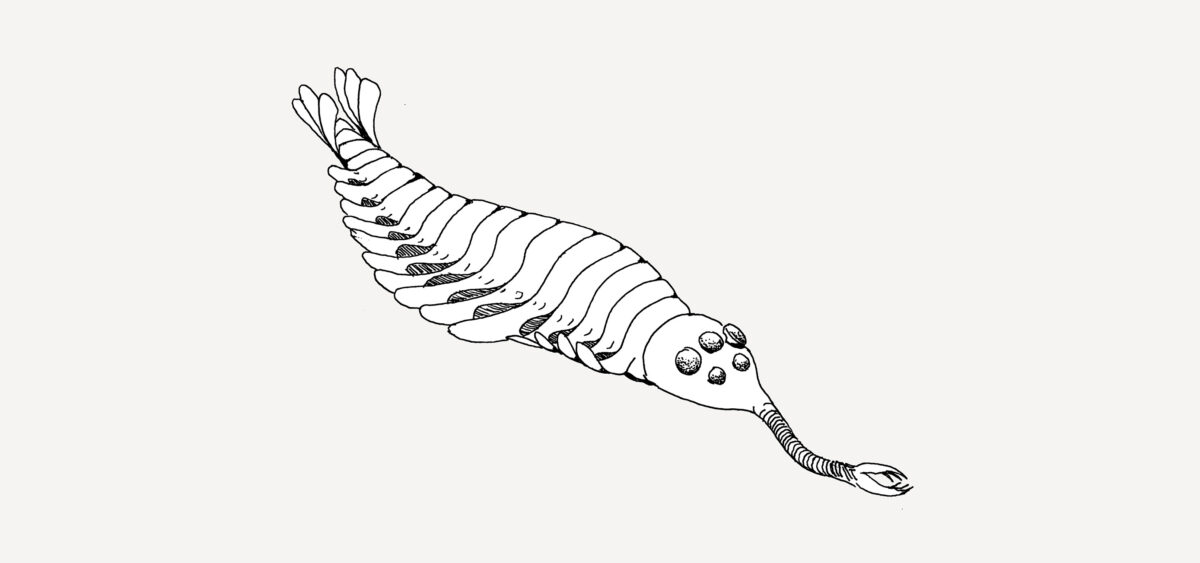

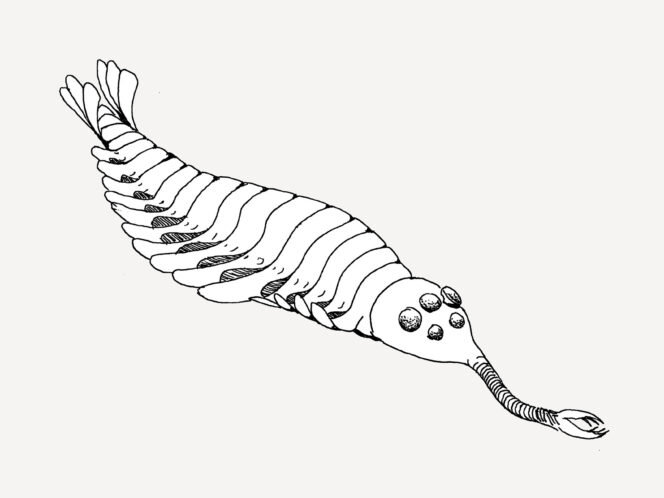

The reconstructions of Cambrian animals were so strange that at scientific conferences they aroused widespread mirth: Opabinia (an arthropod) had five eyes on stalks and a trunk, ribbed like a vacuum cleaner pipe, with a grasping jaw at the end. The name Hallucigenia speaks for itself; this animal resembled something one would usually only see under the influence of LSD.

If, with our geological hammer in hand, we examine rock layers from the oldest to the youngest, we will notice an amazing phenomenon: in the earliest layers, with the naked eye, we will not see any signs of life; no fossils. However, from a certain moment, on a line in time as sharp as a knife, incredibly rich forms of life appear. This is the Cambrian world, a geological period that began 541 million years ago and lasted just over 55 million years. The demarcation between the Cambrian and the previous period, devoid of any signs of life, is so marked that this phenomenon acquired the description ‘the Cambrian explosion’.

Family excavations

“Camping in the Canadian Rockies is a relatively simple affair if one is accustomed to going about with saddle and pack animals for conveyance,” wrote the American palaeontologist Charles Walcott for National Geographic in 1911. Two years earlier he had discovered an extraordinary palaeontological site in those mountains: the Burgess Shale. The uniqueness of this place rested not only on the fact that the