What is colour? For a physicist, it’s a measurable unit of electromagnetic waves of a certain length and frequency. For a chemist, colour comes about as a result of a chemical reaction between two or more elements. For a student of anatomy, the impression of colour is created when a stimulus is received by the visual apparatus, which sends a signal to the brain, where it is processed. For some, colour exists as a fact, for others, it’s nothing more than a subjective experience. And so, how should colour be measured, named and organised into a system?

A natural spectrogram of colour is a rainbow. Isaac Newton greatly contributed to how we think about colour by establishing an arbitrary division between spectral colours, known by their simple, graphic representations, such as colour wheels. Colour wheels offer quite a limited array of colours based on the colours we see when we look at a rainbow: usually, red, orange, yellow, green, aquamarine, blue and purple. Yet the human eye is capable of distinguishing hundreds more.

We’d see an even greater range of colours if it wasn’t for the fact that the human eye is only capable of receiving a certain range of electromagnetic radiation, fittingly referred to as the anthropocentric notion of ‘visible light’. Evolution has made it so that our visual capabilities benefit from only the narrow scope between ca. 400 to 700 nanometres. A broader scope, containing shorter and longer wavelengths, would give us even greater capabilities, such as the ability to see through walls.

In comparing the visual capacity of a human being with that of other beings, how much is our perception of the world determined by the physiology of our species. Certain invertebrates, such as the mantis shrimp, has over a dozen types of photoreceptors (rods) in its eyes, when a human eye has only three. The scope of this creature’s eyesight spans infrared, ultraviolet and polarised light. We’re not even capable of imagining how the world of colours might appear through the eyes of the mantis shrimp. And could these colours be named using our existing lexicon?

The methods of cataloguing and naming colours reflect the way in which colour was thought of in a particular period in history. They were often named for the substance that brought about a particular hue or the name of a plant of that colour. In Polish, the colour pink is named for a rose (róża), violet for violets (fiolet), red (czerwień) for the larvae of the beetle of the same name, which was the source for making dye of a red colour. The poetic title Colour of Lost Time comes from an 18th-century French fashion magazine. We don’t know what that colour might be, perhaps it was a certain shade of blue. Today we use colours and symbols to indicate a particular hue in various colour coding systems.

What is colour for an artist? It certainly makes the foundation of their artistic expression, broad enough not only to describe the form of a work of art, but also its message, which can touch upon various emotions related to colour. Do artists need a precise system for naming colours? Perhaps, like Bownik, they want to blur the certainty (which is never fully certain in any case) we have about the colours we see and what we call them.

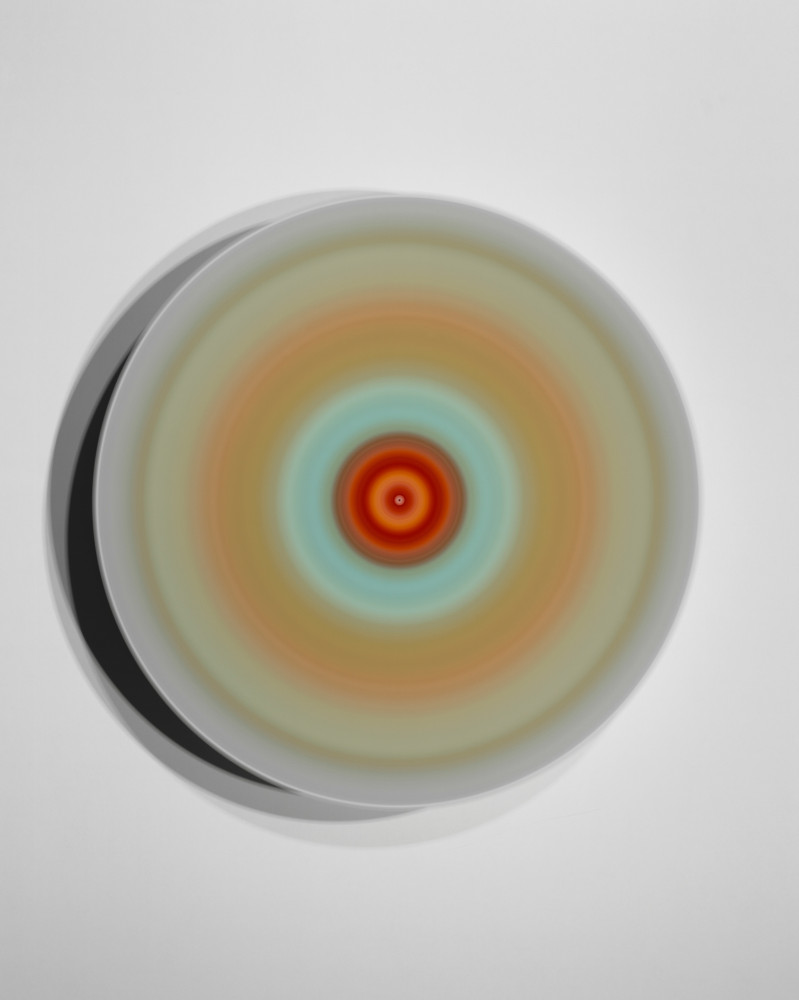

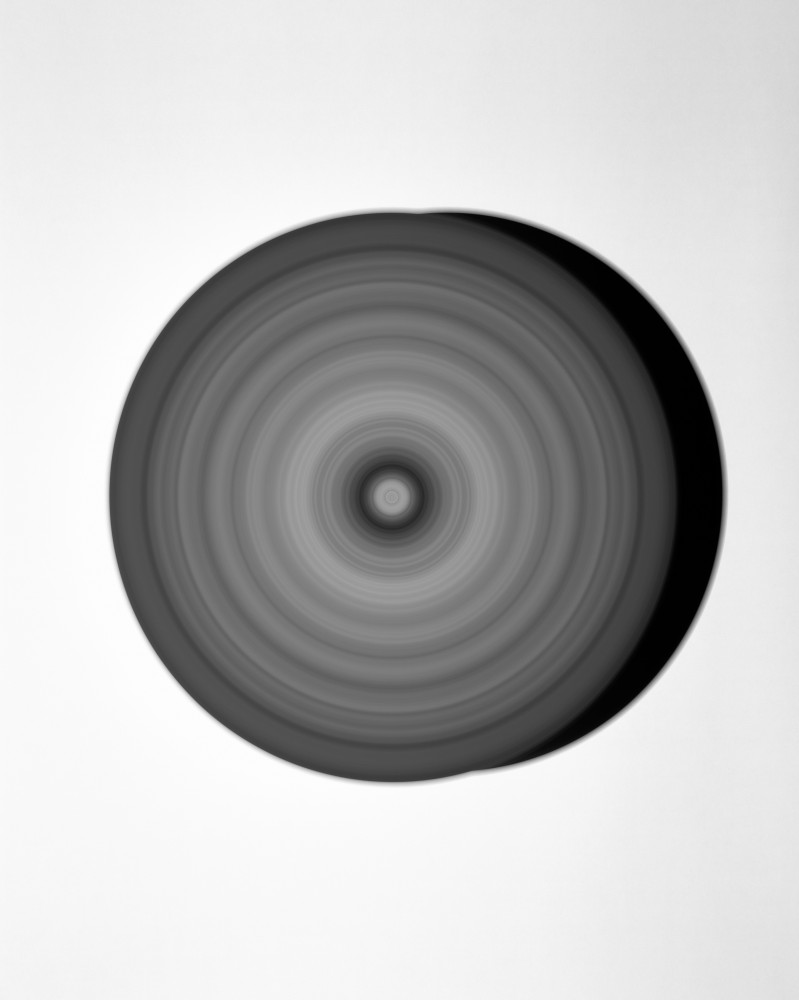

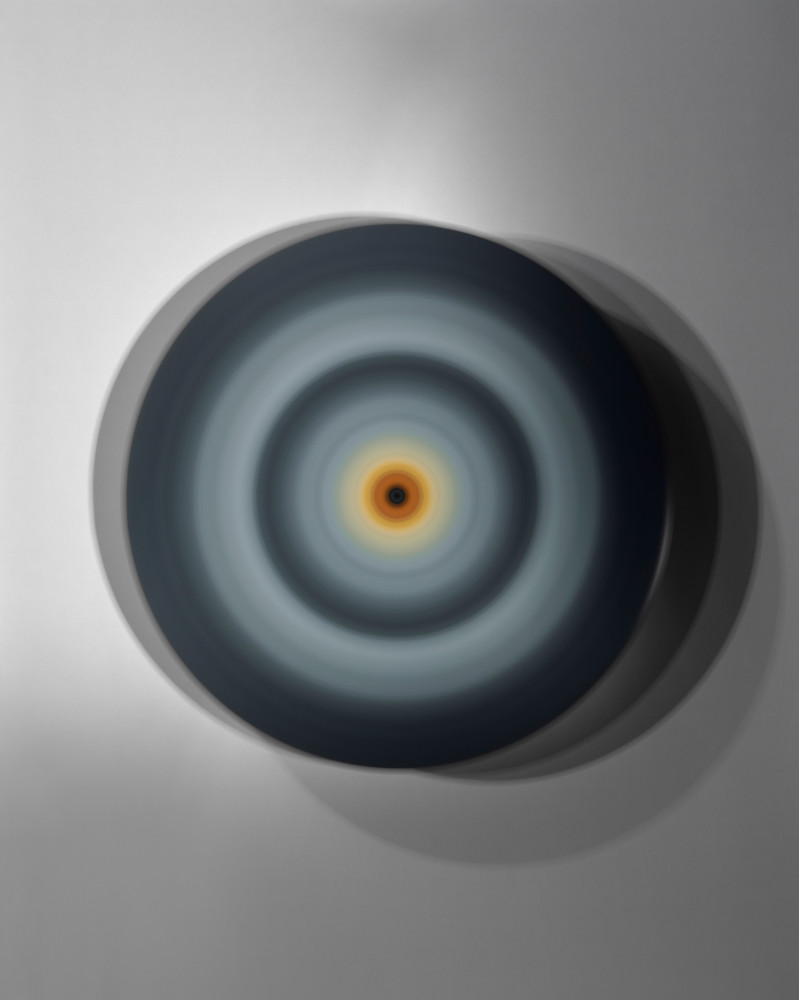

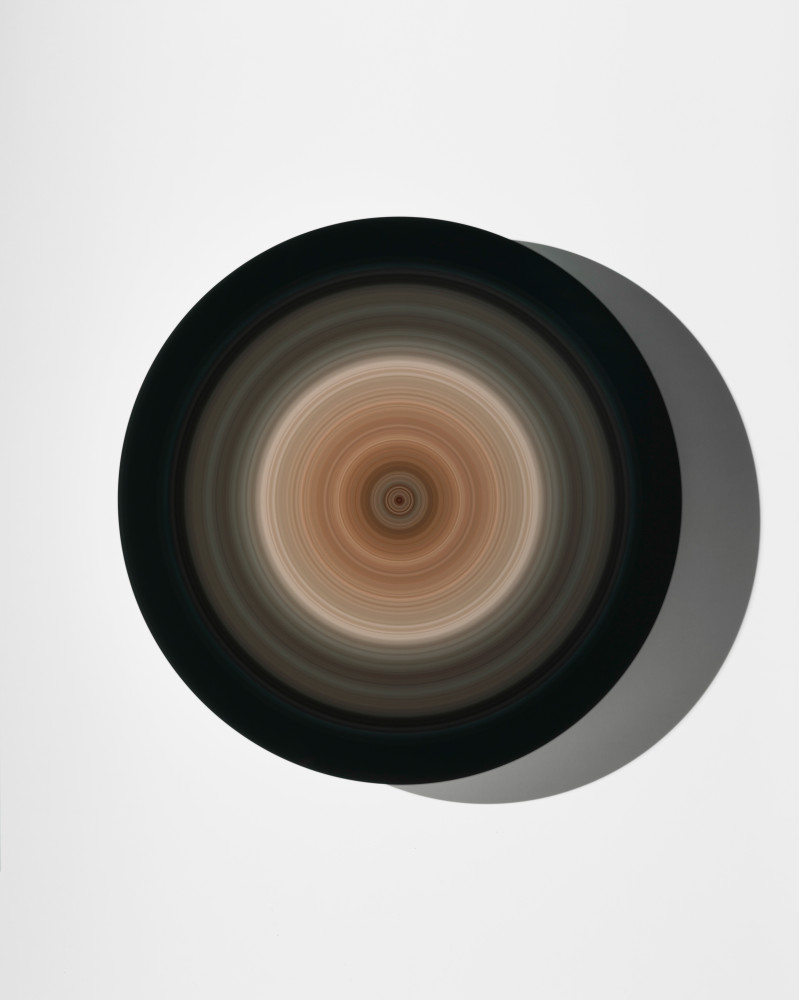

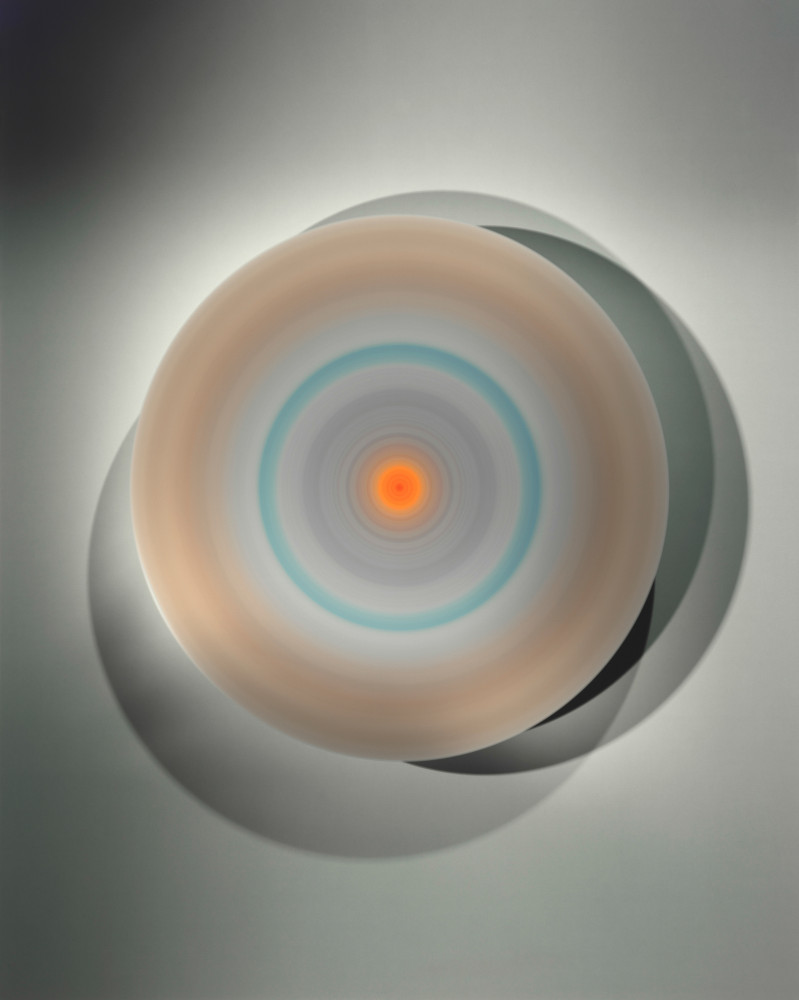

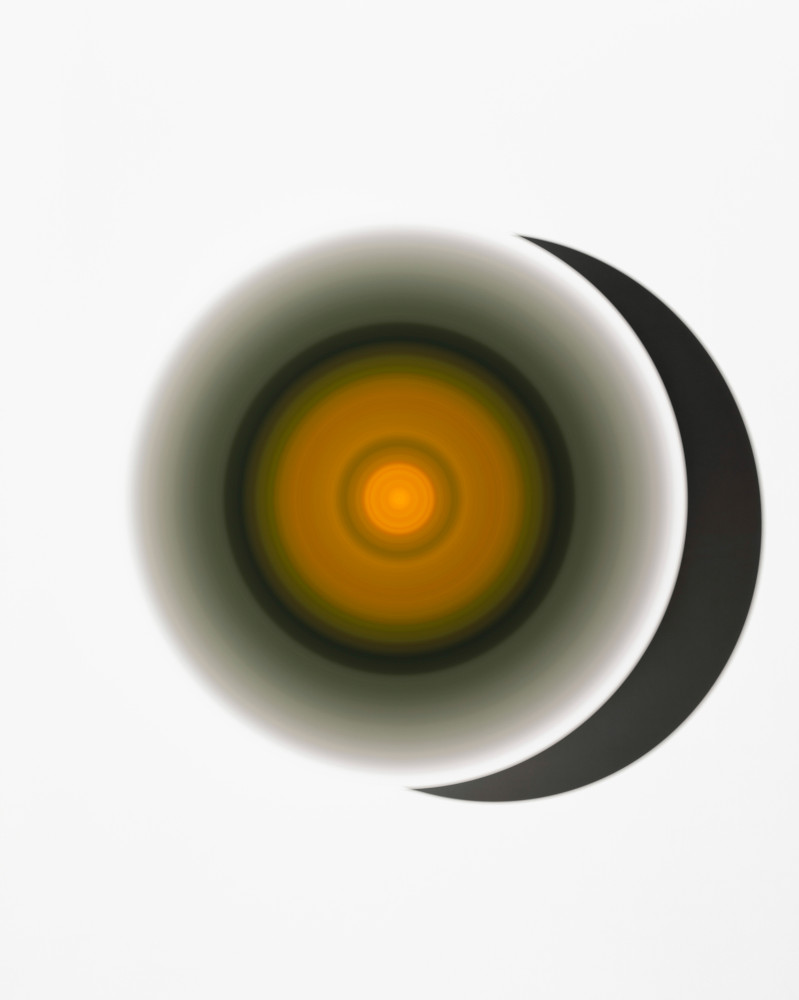

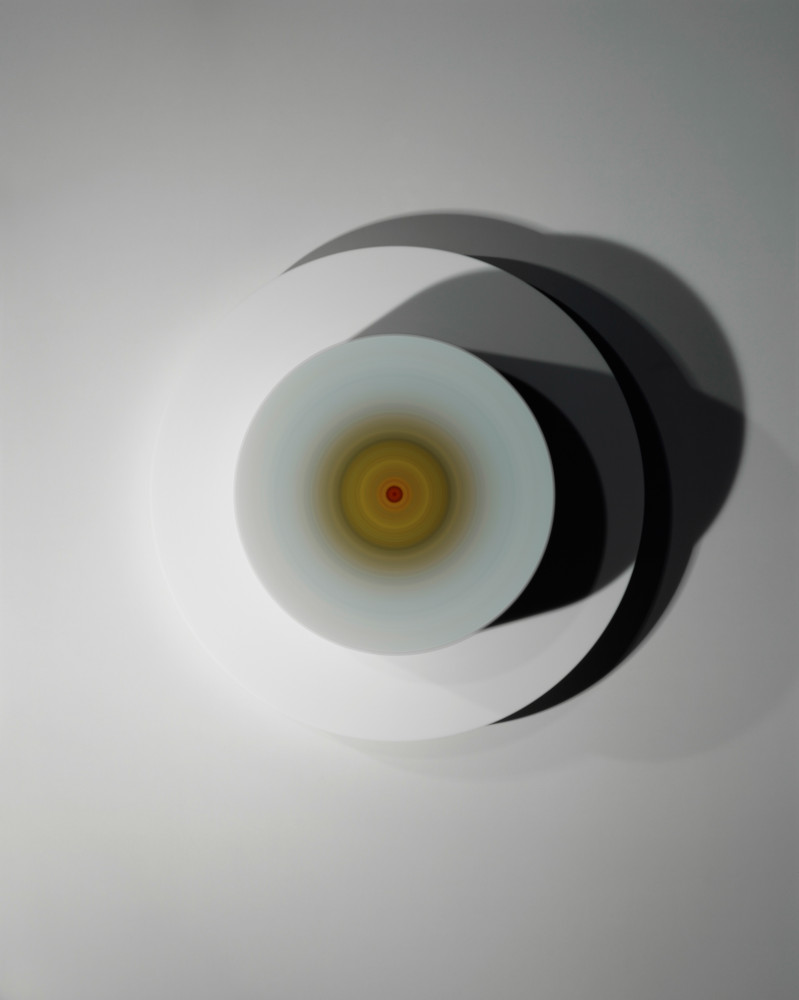

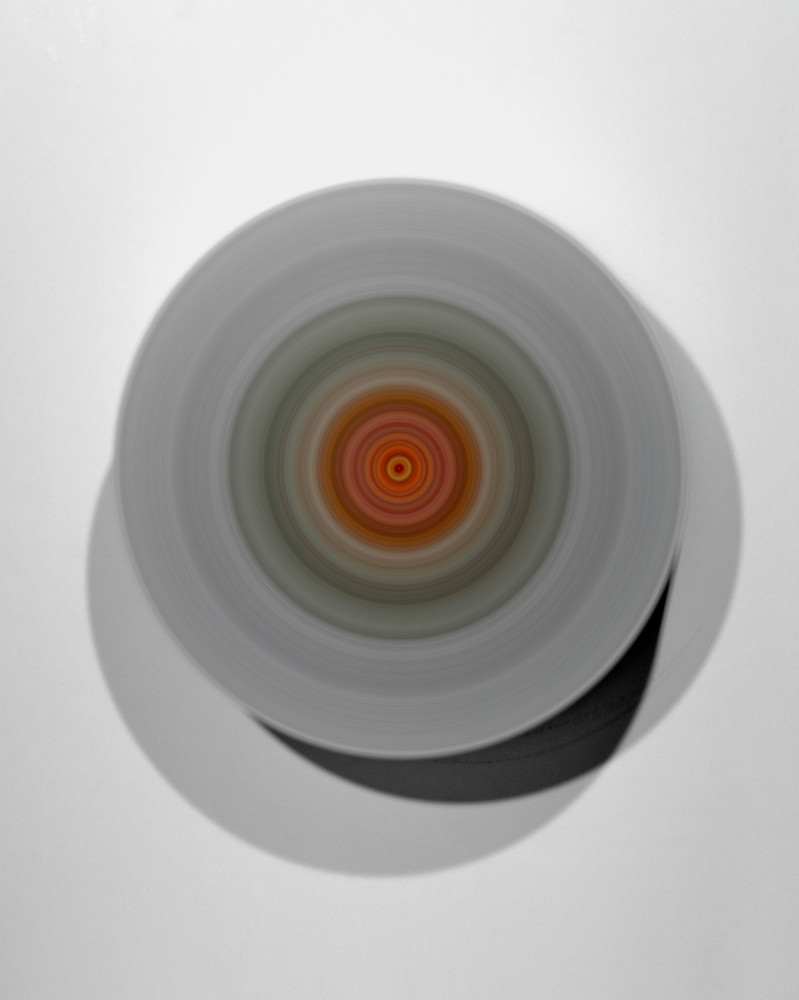

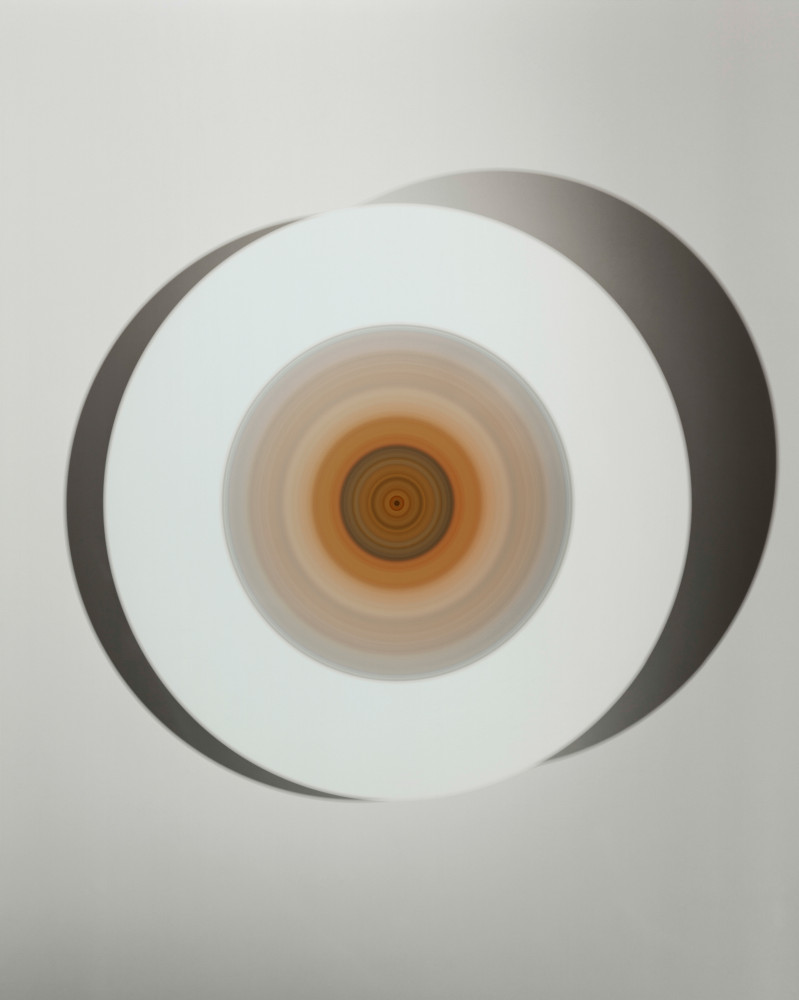

Some of Bownik’s works suggest their own, independent colour wheel. And, yet, there aren’t in any way put into order or regulated in any way. The colours that filter through them have no name, but also – like with a rainbow – they have no defined limit between them. They take on subtle hues that come together in an inconspicuous way. These aren’t the tones and colour matches of our everyday lives. Their vibrating, impossible to define, character is underlines by the rough texture of the paper they are splayed across.

Each wheel came about as a photograph of a rotating disk, photograph or etching depicting a single bird. What’s more, this is a bird that doesn’t exist any longer. Bownik’s vision takes the intense, saturated hues of a bird’s plumage and has them disperse, turning them into a buzzing phantom of spectroscopic dimensions. These extinct creatures come back to life in the form of a mysterious spectrum that casts shade. Each ‘wheel’ in the series is numbered, even though it is the transposition and artistic record of a particular species of extinct bird. These phantom birds no longer have their own names, much like our dictionaries don’t contain all the colours of lost time. Time devours its own children, as well as the memory of them.

Grażyna Bastek

Bownik (born 1977) graduated in Philosophy from the Marii Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin and in Photography from the Academy of Arts in Poznań. His best known works include the photographic series Gamers, Słodowy, Koleżanki i koledzy, Disassembly, and Rewers. The authorial photobook entitled Disassembly, published by Mundin, won the main prize in the competition Fotograficzna Publikacja Roku 2014 and received nomination for the Kassel Photobook Award 2014. Bownik’s works may be found in the collections of e.g. Museum In Huis Marseille in Amsterdam, ING Polish Art Foundation, Zachęta National Gallery of Art, as well as in private collections.