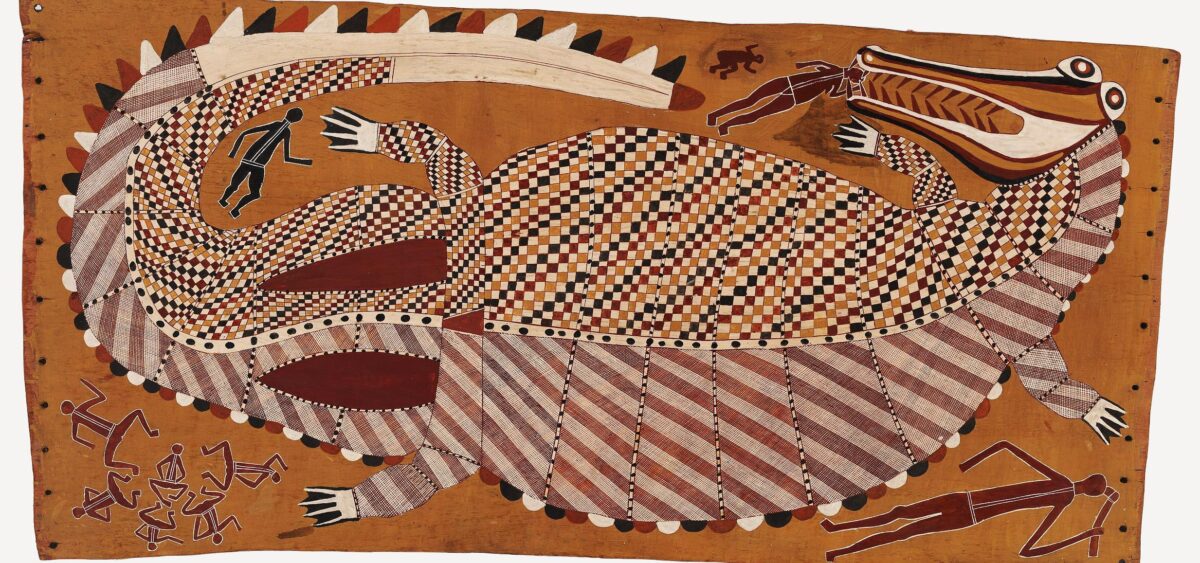

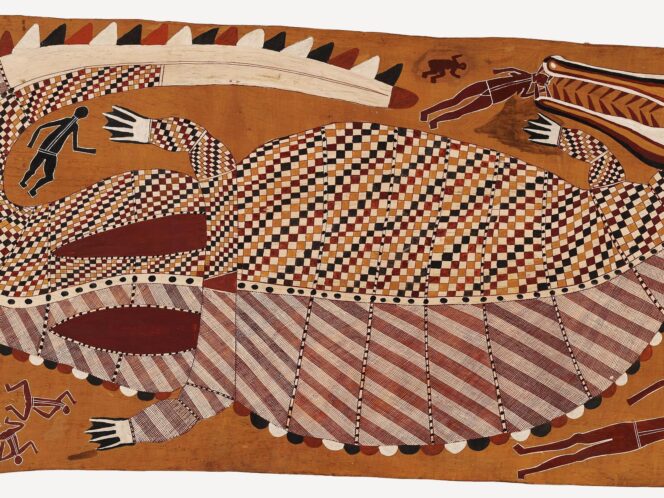

For decades, Aboriginal art was pushed into a drawer labelled ‘primitive art’, treated as part of the realm of ethnography or the souvenir industry. Nowadays, works by Pintupi painters from Papunya are considered the most important achievements of contemporary art in Australia. While it fits into the context of aesthetic trends and artistic controversies, Aboriginal art remains an important political voice, also in specific disputes over rights to the land.

Papunya Tula is a sandy settlement in the middle of the desert, located more or less in the heart of Australia. Its name in the Pintupi language means ‘the place where honey ants meet’. At the beginning of 1971, a new teacher, Geoffrey Bardon, arrived there. His pupils barely spoke any English, so he was assigned an interpreter, the Aboriginal man Obed Raggett.

In the 1950s, the Australian government had introduced forcible assimilation policies. Since then, Papunya has been a place where Aboriginal people from various nomadic tribal groups were settled, especially the Luritja and the Pintupi. Their ancestors had been poisoned, starved or murdered in other ways, their land taken away from them and used as new pastures or settlements. To thrive as nomads, Aboriginal people need to be constantly on the move. Not much connected them with Papunya, but they couldn’t leave it without permission from the authorities. Which is why they struggled with accepting the new reality, on top of worrying about the disappearance of their languages and cultures. Bardon compared Papunya to a death camp. At the beginning of the 1970s, its population was about 1000.

In the local school, 14 teachers were teaching Aboriginal children English and the basics of European culture. Education was creating an even bigger gap between the children and their parents, who spoke traditional languages and were rooted in their own culture. Bardon, who taught art among other subjects, didn’t follow the curriculum. He was interested in Aboriginal painting. For example, he noticed that children preferred to paint on the floor and not on tables. When he met them outside of school, he saw that they drew signs and symbols in the red earth, whispering something and clapping while doing it, as if they were telling some kind of a story. At the end, they would erase the symbols in the sand and start everything from