The Saul Leiter exhibition at the FOAM photography museum has a lot to offer. Besides photos resembling paintings, and a slice of New York in the heart of Amsterdam, a reminder that in the age of digital overload, photography can still have a soul.

As the first quarter of the twenty-first century draws to a close, we are approaching the bicentennial of the first image recorded using light: “View from the Window at Le Gras.” French physicist and inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce positioned his camera (a camera obscura loaded with a light-sensitive copper plate) through his studio window, aiming the lens at the interior courtyard of his home.

What does the image show? Very little today—just enough to distinguish the shapes of the buildings. Deep shadows fall from two opposite directions of the eight-hour exposure, creating an unreal view—a mix of the sets from the film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and the paintings of Braque’s early cubism.

Today it is hard to imagine that in 1827, this was the only photograph of reality in the world. A mummified day, a packaged fragment of time and space, transported to another dimension.

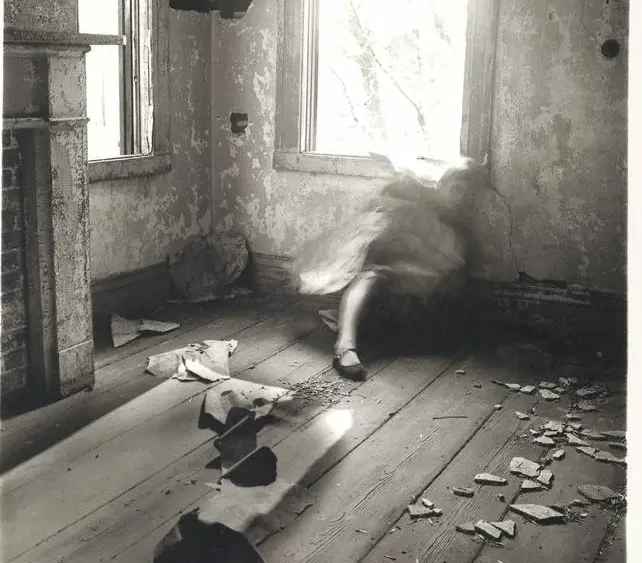

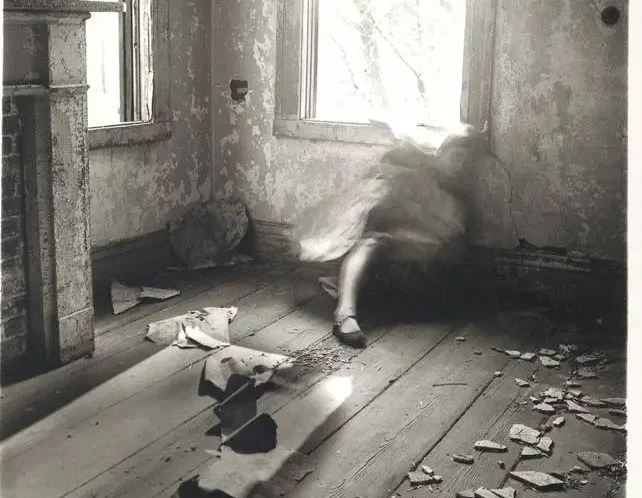

While there are no figures visible in the photograph, it does reveal the soul of its creator. His life’s work is contained in the apparitions of those houses. In that languorous afterimage that Niépce might have seen when he looked out the window before closing his eyes and dreaming of how to capture it.

I have the same experience as I drift off to sleep at 7:30 am on my way from Warsaw to Amsterdam. The view from the window in a plane above the clouds. Sunrise and a thought: without a chemical smell, real photography does not exist. The last vapors are still hanging in the air, but our lazy habits are disturbing its reception. Today we do not take photographs with “the pencil of nature,” to cite William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the pioneers of photography. We extract them from something that was