For John Cage, music was more than just notes. It encompassed everything, from cacophony to silence. He considered his sound experiments to be part of the Buddhist practice of transcending the ego, which is why he relied on pure chance while composing, often quite literally—by rolling dice.

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few,” claimed the Japanese Zen master Suzuki Shunryū (1904–1971), one of the first ambassadors of Buddhism in the West. The quote appears in the compilation of his talks, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Suzuki suggests that the beginner’s mind is open, spontaneous, ready to take in whatever is happening at a given moment. The expert, on the other hand, tends to sink into routines and react according to established patterns. The beginner’s mind says “I don’t know,” whereas the expert’s mind says “I know better,” which is why the former is limitless and the latter is limited. Like all Zen teachings, this basic lesson appears to be both utterly simple and very difficult. It isn’t about refusing to develop skills or knowledge—the challenge is to preserve an ebullient, unprejudiced attitude towards oneself and life while making progress at work, in studies, or in daily practices. One can be a virtuoso in a certain field while remaining a “beginner”; some may understand very little, yet speak like “experts” whose relationship to the world is blocked by an excess of opinions, beliefs, and preferences.

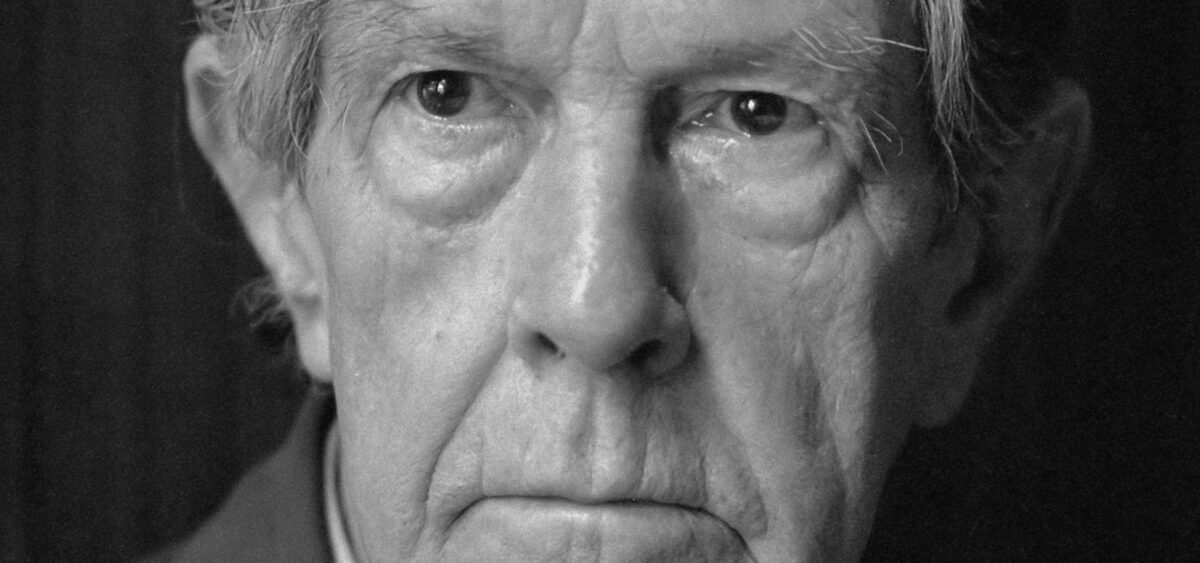

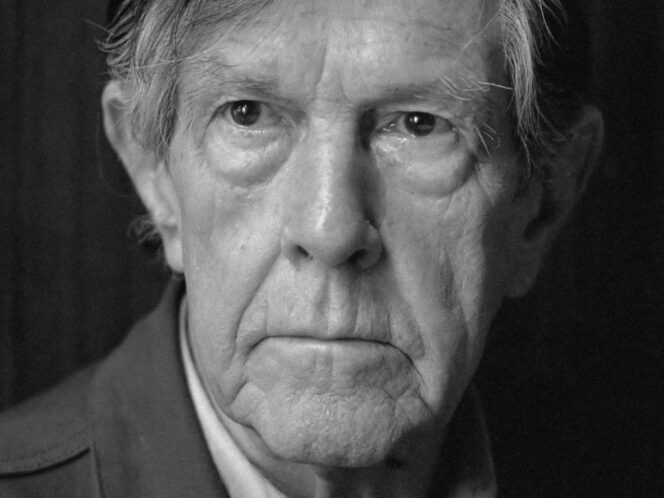

“I try over and over to begin all over again,” John Cage (1912–1992) used to say about himself. He was a composer, poet, performer, and choreographer; “a theoretician of society and the arts of the future,” as the publisher of the Polish book Przeludnienie i sztuka [Overpopulation and Art] described him. An&nb