The 2021 National Census is well underway in Poland, yet there is a group of people unlikely to be picked up by it. The Karaite minority are simply uncountable.

The smell was novel. The freshly printed book had just arrived and Anna Sulimowicz was unboxing the package with excitement. She tenderly turned the red cover with an illustration of a Turkish carpet to see the first page:

Orhan Pamuk

Silent House

Translated by Anna Akbike Sulimowicz

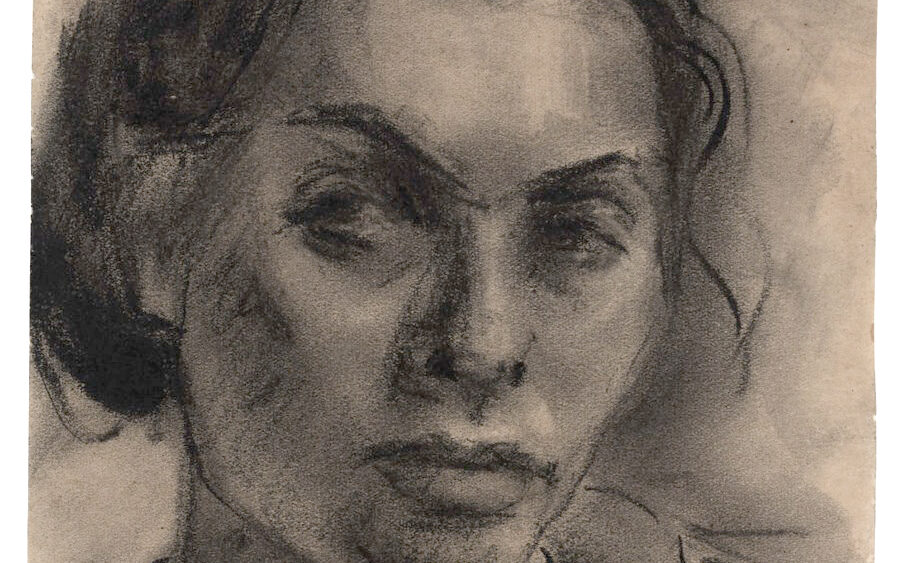

Anna held her breath. Akbike is a Karaite word meaning, literally, ‘white queen’. She hadn’t heard that name since her early childhood; it was what her father and his friends used to call her. But she had never used it in her adult life. She immediately phoned the publishing house to ask for an explanation. “They told me that the name had been copied from the translation agreement we signed,” Anna recalls, more than 10 years later. “Obviously, such agreements must be in accordance with my documents. On my birth certificate and my ID card, I am officially called Anna Akbiké Sulimowicz.”

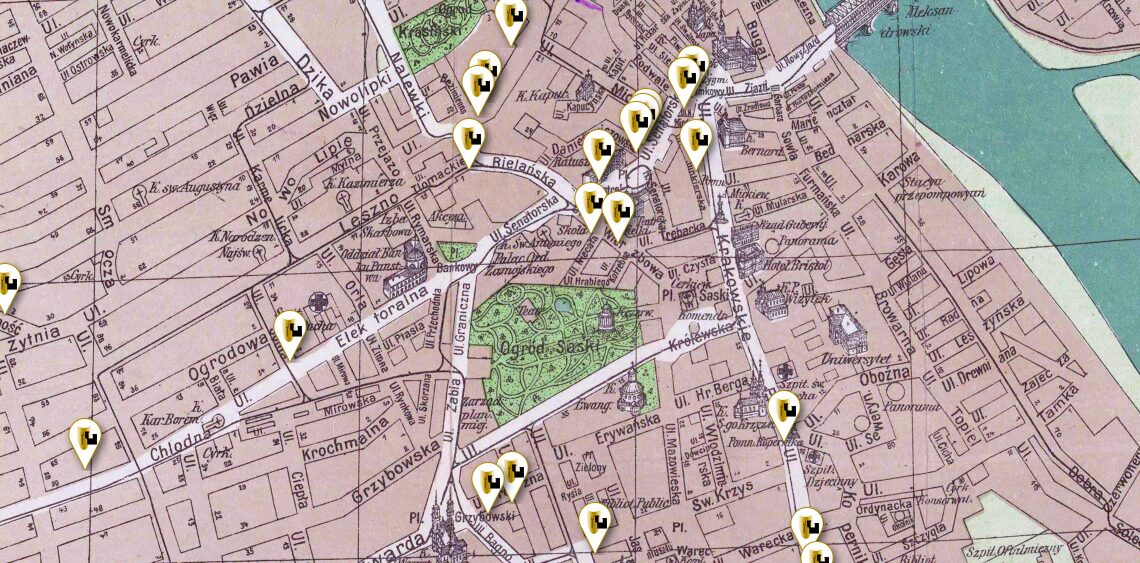

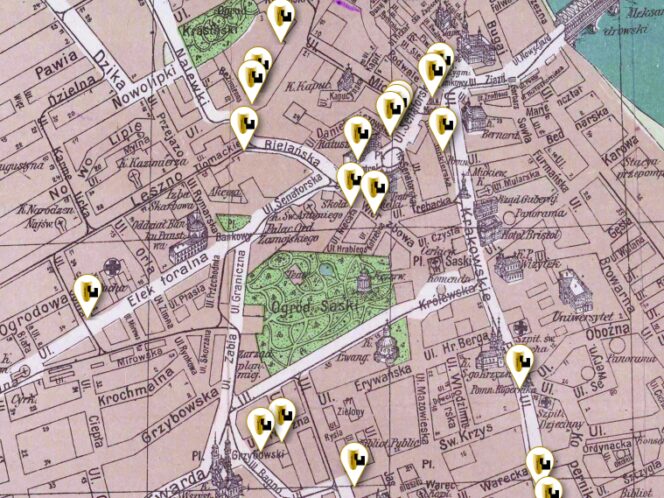

Anna is a translator and a lecturer of Turkology at the University of Warsaw. But our conversation is not about Turkey; it is about her other area of expertise – both academic and personal. As we talk, Anna looks around her home office in Warsaw, in a vain attempt to find the book that accidentally informed the public of her true identity. Her office is filled with books, some of which belonged to her father, Józef Sulimowicz. “He was a bibliophile and had a collection of old prints, manuscripts and everything connected with Karaites,” she explains, referring to the smallest of Poland’s ethnic minorities.

Anna is Karaite too – or Karaim in Polish – through her father’s side of the family. Her middle name, ‘Akbike’, was chosen in honour of the mother of Seraya Shapsal, a historic leader of the Polish and Lithuanian Karaite communities. Her first name is common enough, but it, too, carries some unique Karaite traits. “I was named after my father’s sister, who was named ‘Anna’ after her grandmother,” she says. “It is a Karaite tradition to inherit the name of a deceased relative or ancestor.”

Alongside the Roma, Tartar and Lem