Out of the four human temperaments identified by Hippocrates, the easiest to identify are the choleric and the phlegmatic types. In fact, since Hippocrates’s times, they have usually been depicted together. Here lies the key to the last and perhaps most interesting temperament—the phlegmatic.

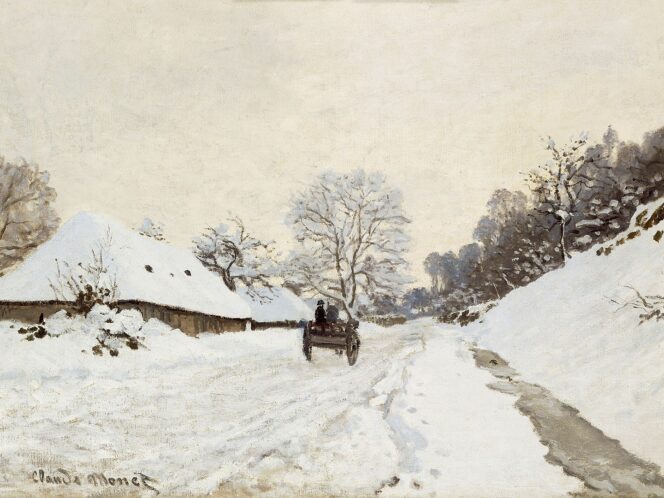

The choleric is the kind of person that summer makes impulsive, angry, but also persevering. Work-wise and emotion wise, the sunny heat is the guiding spirit of fierce personalities who do not find peace as easily as others. As such, the choleric temperament ostensibly has little in common with the peaceful phlegmatic, whose existential kingdom is, conversely, the winter season. Yet, in spite of their apparent differences, they might share something in common.

The Winter Mirror

Hippocrates and his followers did not observe people themselves, but everything around them: the natural world, of which humans, according to the ancients, have always been an integral part. The human being was lodged in their minds like a piece of a much bigger puzzle, seamlessly fitting into nature. For this reason every discovery made about Homo sapiens