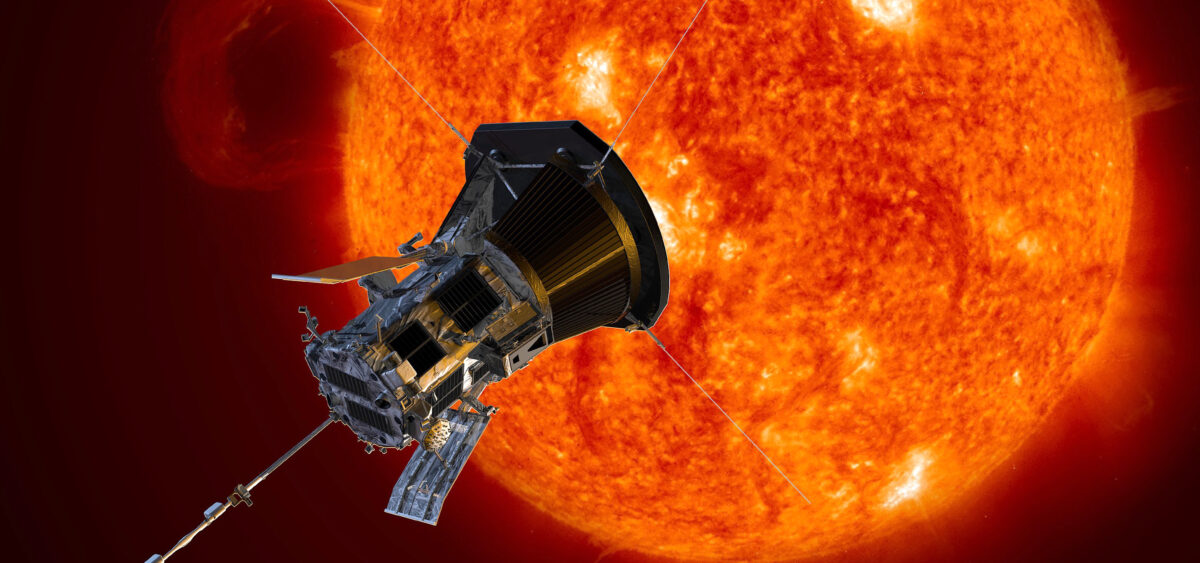

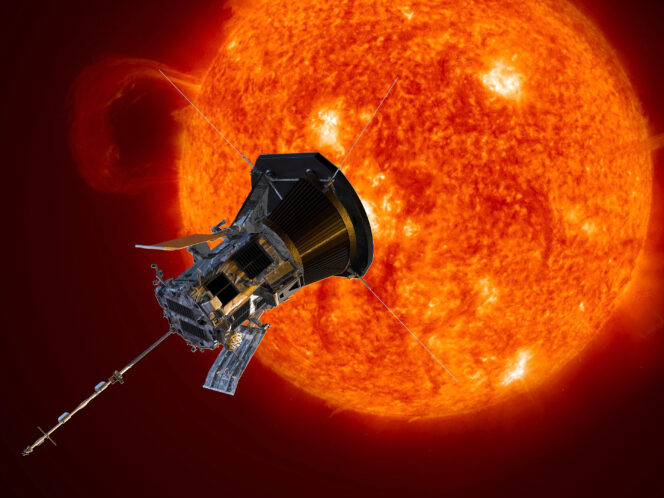

To Touch the Sun

On June 1, 2022 the Parker Solar Probe sent by NASA flew through the corona, the incredibly hot outer layer of the sun’s atmosphere, for the fifth time. The corona’s high temperature—1.8 degrees fahrenheit—is a mystery to astrophysicists. It is hard to say why the layer is so hot, while the temperature of the sun’s surface is only around 9,932 degrees. It’s a bit like using a stove to heat a room to a temperature many times higher than that of the stove itself.

For anyone asking how it was possible for the Parker probe to withstand the temperature of 1.8 million degrees fahrenheit in the solar corona, here is the answer: the temperature there is indeed very high, but the density of matter is low, so the heat doesn’t do so much damage. You could put your hand inside a hot oven and hold it there for a while, even though the temperature inside is 350 degrees fahrenheit or more. If, however, you unwittingly touch the oven walls or a heated dish, burns await. This is the Parker Solar Probe’s secret: it does not touch anything, it only flies through the sun’s atmosphere, which is trillions of times less dense than that of the Earth. As a result, the Parker Probe doesn’t melt when it enters the solar corona. Still, the low-density but extremely hot atmosphere requires the probe