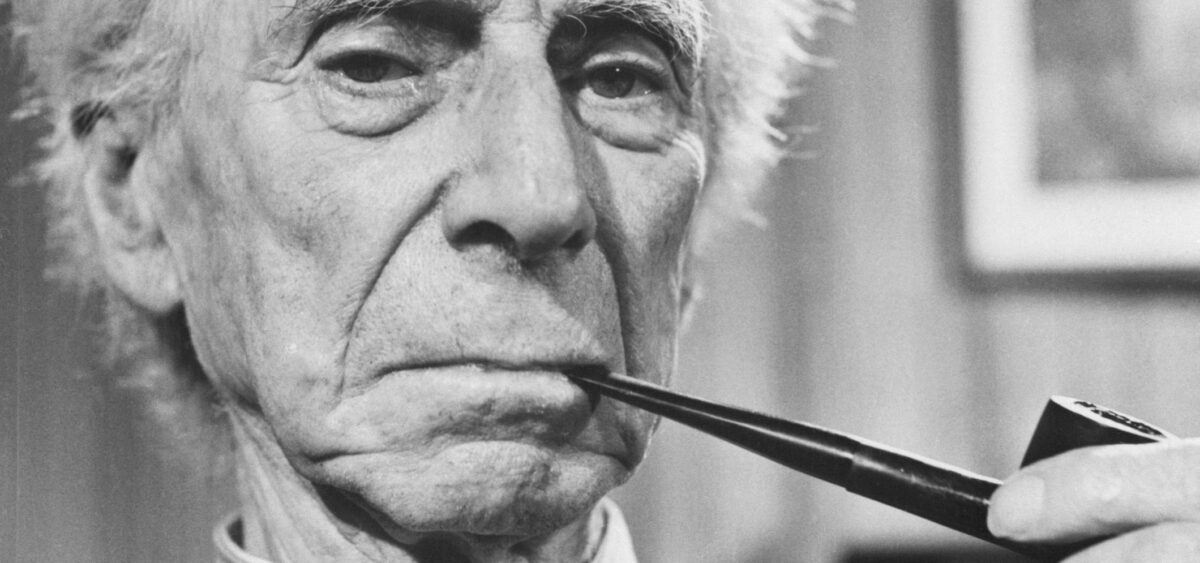

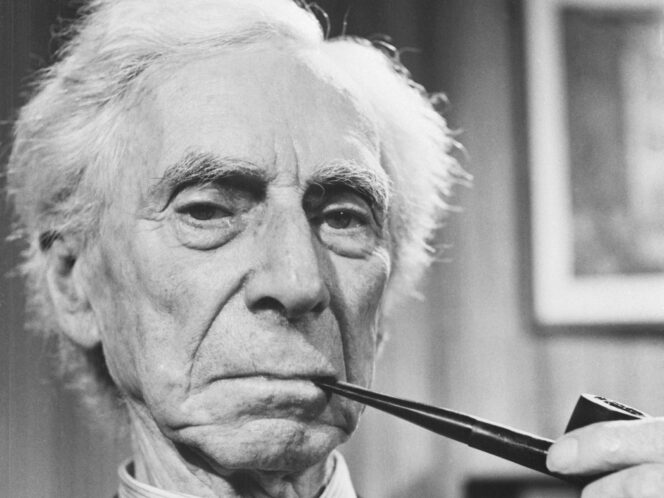

Today’s world could use a philosopher of Bertrand Russell’s caliber—a grand-scale thinker and champion of ideals. An advocate of hope for a better future, he could speak to the masses. Since no such person looms on the horizon—hopefully, just for now—the time is ripe to recall the wisdom of the dead master.

Born in 1872, Bertrand Russell lived a long and fascinating ninety-eight years. He was a giant by the standards of his era—a time of great societal breakthroughs and fantastic ambitions. For this reason, studying his biography, work, and beliefs leads to worrying conclusions. It seems difficult to imagine such a titan being born today; even if they were, they would not be taken seriously. His unwavering hope in ethical progress would be ruthlessly torn apart by armchair philosophers on social media. His deep faith in facts and their meticulous analysis would have fierce enemies among peddlers of conspiracy theories. His ideas delineating humanity’s common and noble tasks would meet with a calculated shrug of shoulders among the pragmatists running the global corporate economy. Even his moral progressivism and enthusiasm for freedom in marriage and sex would have to face the conservative bulldozer, which has been zealously reversing, from Asia to the US, the gains won only a few decades ago. Despite his lively mind, curiosity about all spheres of life, and readiness to tackle dilemmas in the spheres of mathematics, religion, and love, today Russell would remain an outsider. Some would respect him, but others would choose unabashed ridicule. This, however, speaks more to today’s triumph of irrationality and cynicism rather than to the lasting value of the British philosopher’s heritage.

In the Name of Self-Suspicions

Russell was the intellectual and spiritual child of an era marked by large quantifiers, yet he undermined all attempts to rigidify humanity and its place in the world. Today humanity is engrossed in fragmentation and individualization. The contemporary reality of bubbles and ideological tribes on the internet would not accommodate Russell’s unifying and universalistic ideas. This certainly does not mean that there is no need for his sweeping theses. The problem lies instead in the fact that today’s intellectual climate inclines one to reject universal authorities and question institutions.

Conflicting socio-political trends have developed in the West. One is the flight from collective values in favor of a belief in the separate and free voices of individuals, for whom expressing their own perspective constitutes the highest value. The other is putting reason and science