The sentimental depiction of the discovery of the New World as a great adventure is one of the biggest lies in human history. This is why it should come as no surprise that statues of Columbus and Cortés are being toppled. During just the first 50 years of colonization, the Indigenous populations of the Americas were reduced by 90%.

In his book Tristes Tropiques (Sad Tropics), Claude Lévi-Strauss rightly observes that the first encounter between Europeans and the Indigenous peoples of America should be considered the greatest adventure in the history of humankind, which is rather unlikely to be measured up to unless some alien civilization pays us a visit someday. It must have been a breathtaking experience to see for the first time the jungle, paradisical coastlines, volcanoes, animals that brought to mind mythology, cities with large markets, and people speaking languages unknown to the colonizers. When Bernal Díaz del Castillo – one of the foremost chroniclers of the conquest – first saw Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec Empire, he thought he was dreaming. During the second and third expedition, Columbus observed his new surroundings so intensely that his eyes would bleed.

It’s worth remembering that in the past most Europeans were separated from radical otherness. In the 15th century, the route to the East was blocked by the Ottoman Empire. Africa, on the other hand, was usually circumnavigated. There was only the distant memory of ‘paganism’, as preserved in the works of Greek and Roman authors.

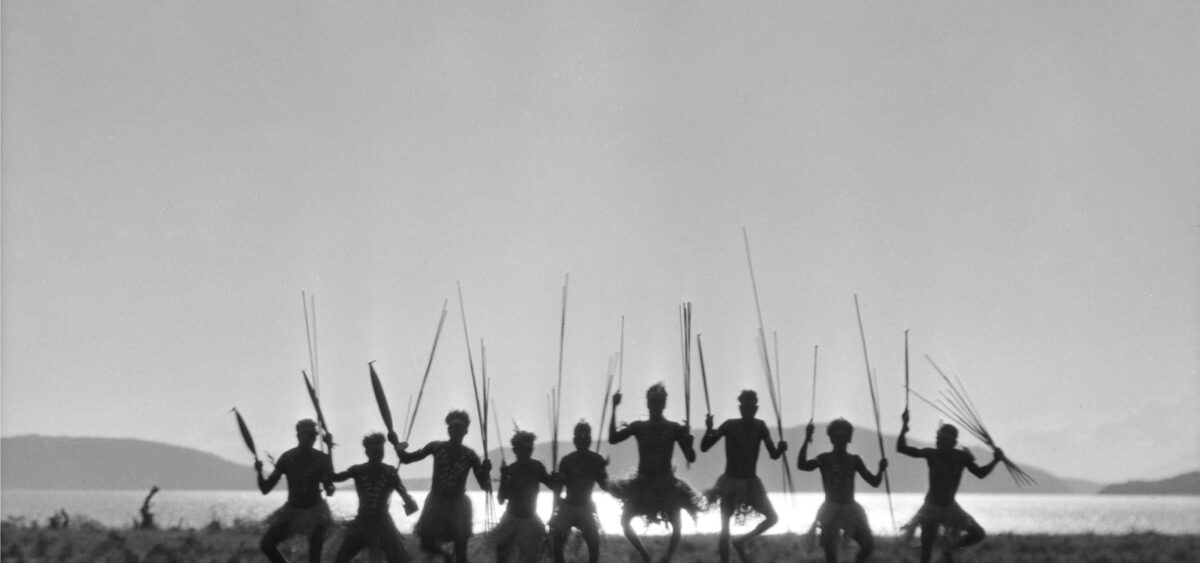

Part of the landscape

Initial descriptions of the ‘new’ societies didn’t herald the genocide that was about to happen: Columbus was convinced that he had discovered a paradise. European institutions tasked with establishing the identity of America’s Indigenous peoples pondered the following questions: were the natives descendants of Israel’s lost tribes? If so, were they Jews (this was the idea of the Dominican monk Diego Durán)? What if they were the exiled Mongols or the Scots? Or the pagans who had been baptised by St. Thomas, but relapsed into idolatry? As Durán claimed, when St. Thomas visited the Aztecs, they thought he was the God Topiltzin, since both were believed to carve in stone.

Columbus’s writings demonstrate that at first he was in awe of the new lands.