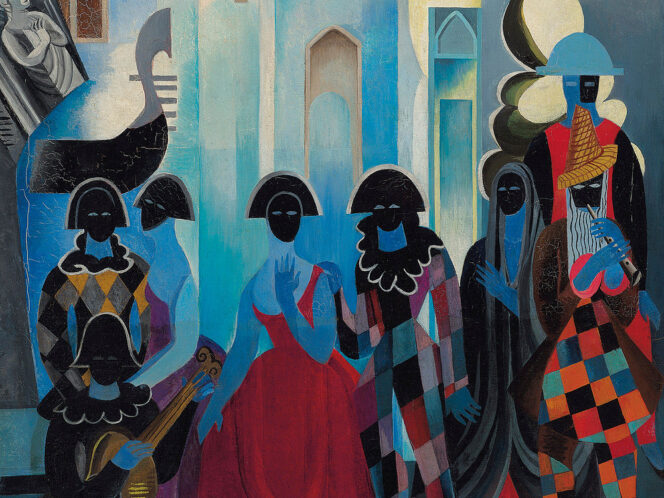

In childhood, we are artists. We draw, dance, make things out of plasticine, without thinking about whether someone likes it or not. With age, however, we lose this joy of creation. How can we learn it anew?

The American psychiatrist and psychotherapist Alexander Lowen was convinced that everyone who creates resembles a child. Creativity results from the need for self-expression and the desire for pleasure. We all have it within us. Małgorzata Karkosz, an art therapist who runs Vedic Art workshops, agrees with this completely: “I believe that we are born with full potential. We are like a lush tree, which over time becomes trimmed according to bonsai standards. It is a paradox: on the one hand, we are under pressure to be creative, and on the other, education and socialization block our creativity.” Art therapy is there to help us.

Follow Your Intuition

“Art therapy is showing ourselves and the world what is within us,” says Karkosz. “Art in the context of art therapy is the voice of the unconscious. Just like dreams, which we also cannot control and which would be pointless to judge.” Participants in her Vedic